One of the common fantasies of time travel is seeing the world change: in a single day, see a small village turn into a sprawling city and then into ancient ruins. Games are a great medium for this effect, since the physical geometry of the world can be explored in great detail, giving the player a genuine sense of visiting a once familiar setting. In principle, this effect can be done without time travel (or rather, with the Linear Time model, that is, simply travelling forward in time). But once the art is done for the past and future versions of the same place, why not let the player freely travel between them? This opens up a huge possibility space: modify something in the past and the future will change accordingly. This page is about those kinds of games.

But first, a tangent: do these games make sense at all? Let’s examine a well known example, Day of the Tentacle. The player controls 3 avatars at once: one in the 2000s, one in the 1800s, and one in the 2200s. At one point, the past avatar makes a change to the design of the American flag, causing the future avatar to see a flag in the future instantly change. Wait, what’s this instantly? Shouldn’t the flags in the future have always used the new design? If the flags are changing due to some time-branching actions that happened 400 years ago, why does it change precisely now? (for the future avatar). Even stranger, how can this paradoxical and contradictory mechanic somehow make intuitive sense and be perfectly understandable?

We need a model of time that properly captures our misguided intuitions about time travel: Serialism. In other words, we will consider the full timeline to be a malleable object that changes with respect to meta-time, the static external time of the real world in which the time travel story is told. The meta-timeline might look like this:

- at meta-time 1, the full timeline looks like this:

- in the 1800s, the usual flag is designed.

- in the 2200s, a flag following the usual design is produced and flown.

- at meta-time 2, the full timeline looks like this:

- in the 1800s, a time traveler arrives via faulty time machine.

- still in the 1800s, the usual flag is designed.

- in the 2200s, a flag following the usual design is produced and flown.

- still in the 2200s, another time traveler arrives via faulty time machine. They observe the usual flag.

- at meta-time 3, the full timeline looks like this:

- in the 1800s, a time traveler arrives via faulty time machine.

- that time traveler messes with the flag design.

- in the 2200s, a flag following the new design is produced and flown

- still in the 2200s, another time traveler arrives via faulty time machine. They observe the new flag.

Each action we perform as players advances the meta-time. At meta-time 2, we perform the action of messing with the flag design, which advances the player to the timeline at meta-time 3. The player goes from the time coordinates “(year 2200s, meta-time 2)” to the time coordinates “(year 2200s, meta-time 3)”; this is a 1-second leap, so it makes sense for the flag to instantly change (these coordinates are for time and meta-time, respectively; don’t confuse them with 2D Time, which is for multiple equivalent dimensions of time). This also answers why the change occurs precisely in the 2200s: that’s the year that we, as players, are observing. The change happens at all moments of the form (year X, meta-time 3), but we aren’t observing those, so we don’t see the flag suddenly jump there.

Note that the avatars controlled by the player might or might not be advancing in meta-time: if they don’t, the future avatar will think that the new design has always been there; if they do, the future avatar will see the flag suddenly change, just like the player. A common trope is for all the in-world characters to remain oblivious of the change (thinking that the new design has always been there), except for the player’s avatars. The original formulation of Serialism gives an answer to this phenomenon: while all material objects change with respect to time, the human soul lives in meta-meta-meta-…-time, meaning that we experience the one and only objective time: if someone were to travel in time and change history, we would advance in meta-time to the new timeline and be aware of the changes. With this explanation, we can imagine that a player gives soul to the avatars they control, making them also advance in (at least) meta-time. This view of players as soul-givers also serves to explain why Record Clones have no free will: the player is controlling a single avatar, meaning that only that avatar is aware of the changes to the timeline.

Anyway, that’s enough of that. Here are some games with this model of time:

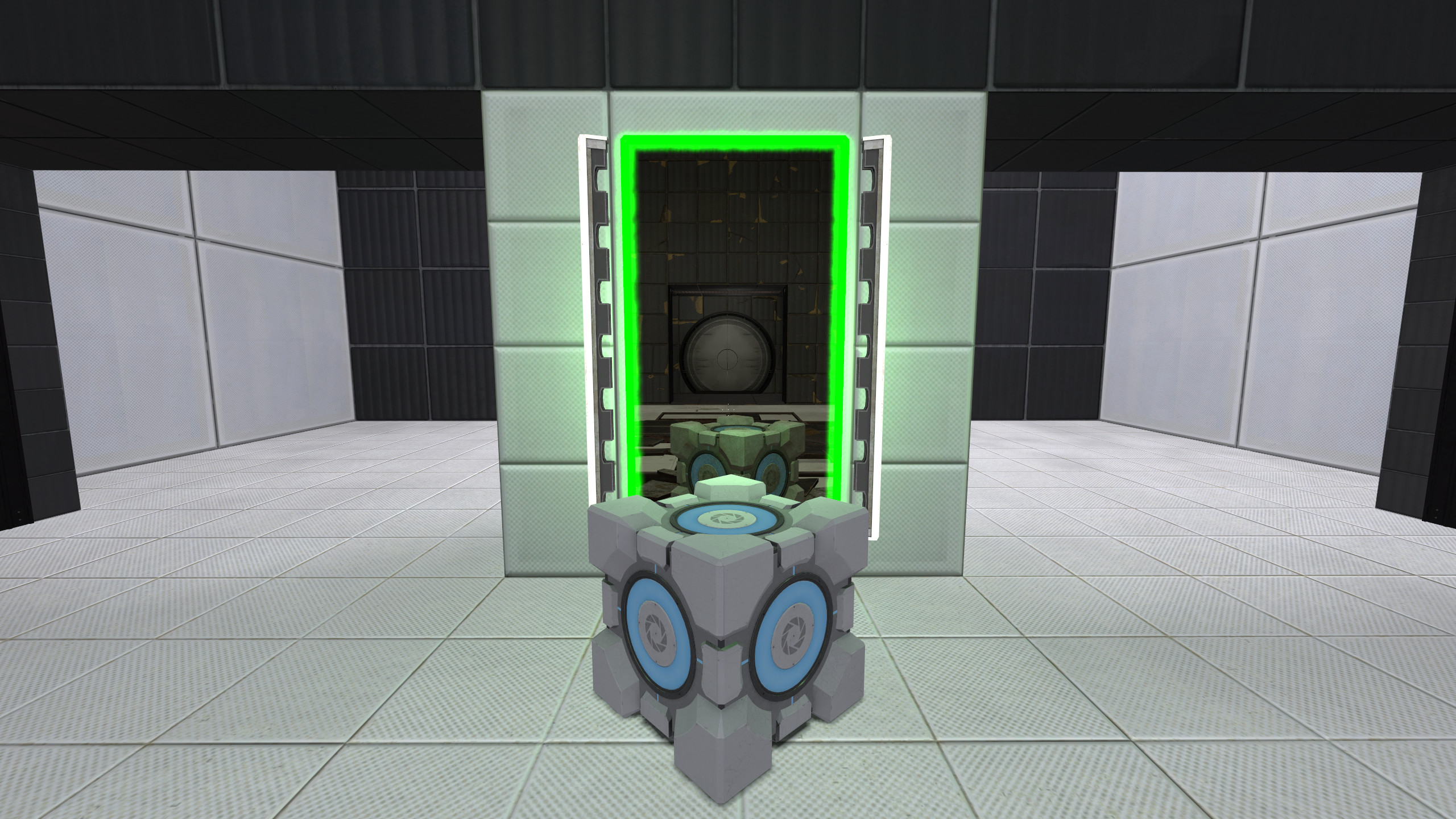

Portal Reloaded by PORTANIS

Free mod for Portal 2 that adds a Time Portal, allowing the player to travel between past and future versions of the same chamber. Changing stuff in the past will affect the future, and you may take cubes back into the past. Puzzles are pretty good, even though there are some unintended solutions and small timing elements. The time travel doesn’t really make sense (why can’t a past cube go into the future?); the levels get easier if you think about them as 2 slightly different rooms with some extra constraints connecting them, instead of thinking about it as time travel. Really challenging but mostly fair. Highly recommended.

Day of the Tentacle by LucasArts

Classic graphic adventure game about controlling 3 characters stuck in 3 different time periods. I haven’t played it.

Banjo-Kazooie - Click Clock Wood by Rare

Classic 3D platforming game for the Nintendo 64. One of the levels, Click Clock Wood, features the same world in all 4 seasons. Changing the season will change the general look and feel of the level (for example, winter features slippery ice). In addition, the player’s actions in one season can affect the next ones: plant a seed in spring, water it in summer, and it will bloom on the fall. I haven’t played it.