Playing with extra spatial dimensions is always fun. Will we get the same flavor by playing with extra temporal dimensions? By this, I don’t mean having 2 time-like dimensions in General Relativity (which is explored in Greg Egan’s Dichronauts). Rather, I mean that objects have “worldplanes” instead of worldlines, or in other words, that we must ask “Where is the object at time (t1, t2)?”. This extra time coordinate has a lot of unexpected effects; let’s explore them! TLDR: the end result will be pretty disappointing, but the road to get there has some interesting twists.

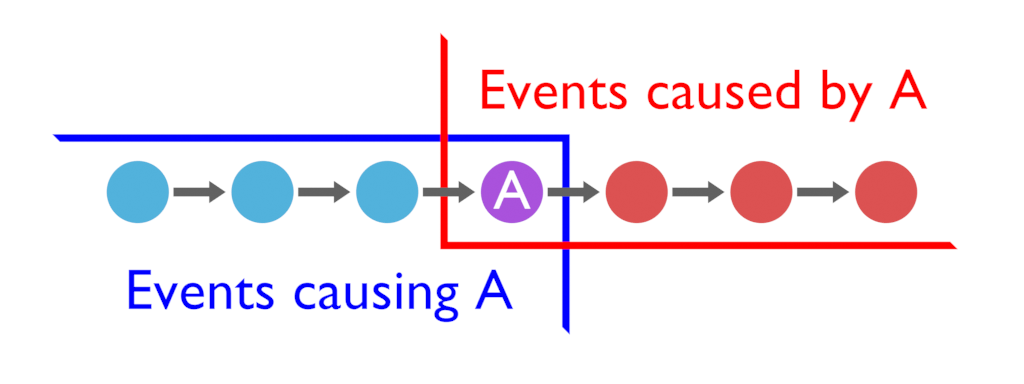

Let’s start by making some diagrams. One-dimensional time might look something like this:

Each circle represents an event, and the arrows represent causality. The event A is caused to the event to its left, which is itself caused by the event to its left, etc. The event A also causes the event to its right, which will cause the event to the right of that, etc. Taking A as a reference point, all events are cleanly divided in two groups: those that cause A (the past), and those caused by A (the future). (Sidenote: if you know about relativity and light cones, this is a good moment to forget about them. “Speed of causality” doesn’t apply since these diagrams have zero spatial dimensions, so all events are either in the past or in the future of A, there are no events elsewhere)

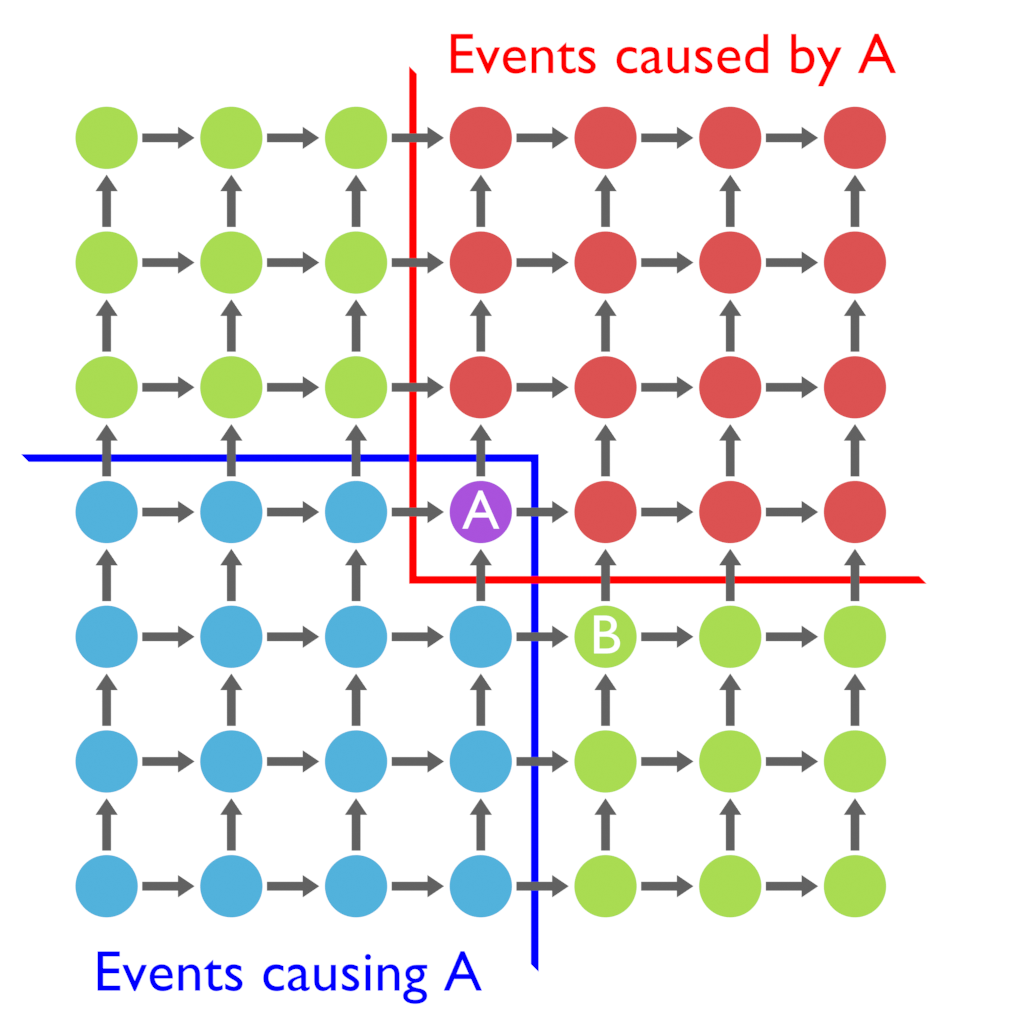

Simple enough. Let’s add an extra time dimension to the mix:

Causality now advances in two directions: left to right, and down to up. The first notable effect is that time no longer divides cleanly in Past and Future: there’s also the Weird Present. Let’s consider the event B: B can’t cause A, since A happens before B (with respect to horizontal time), and B can’t be caused by A since A happens after B (with respect to vertical time). We will say that B is in the Weird Present of A, meaning that there is no causal chain between A and B. Does this mean that these two events are completely independent? No: observing one will tell us information about the other. To see this, consider the following example:

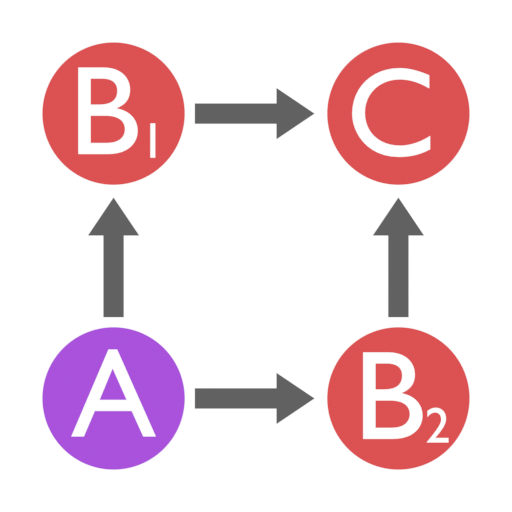

We start at A, wait a second in either direction, and flip a coin. At first sight, B1 and B2 seem like independent events (since no causal chain connects them), so we could get heads in one and tails in the other. But then, what state will the coin have at C? If some irreversible action depends on the coin’s result, then the coin must give the same result at B1 and B2. Thus, the states are correlated: knowing one tells us all about the other. This is a good moment to feel cheated: our fancy 2-dimensional timeplane A-(B1-B2)-C seems to have collapsed into a boring 1-dimensional timeline A-B-C.

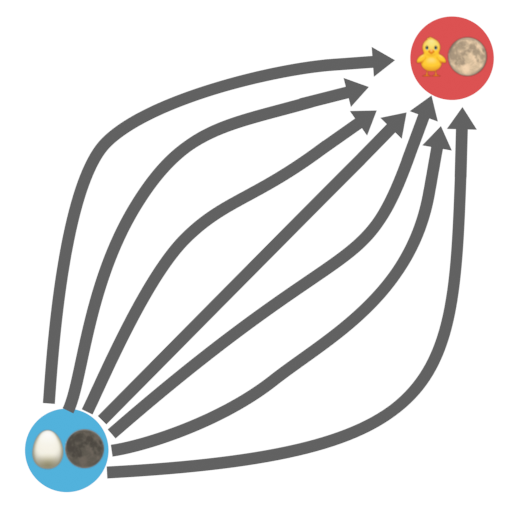

This collapse isn’t a bug, it’s a feature. We feel cheated due to a wrong assumption: seeing events as points. Let’s draw some of the causal chains between 2 points in time:

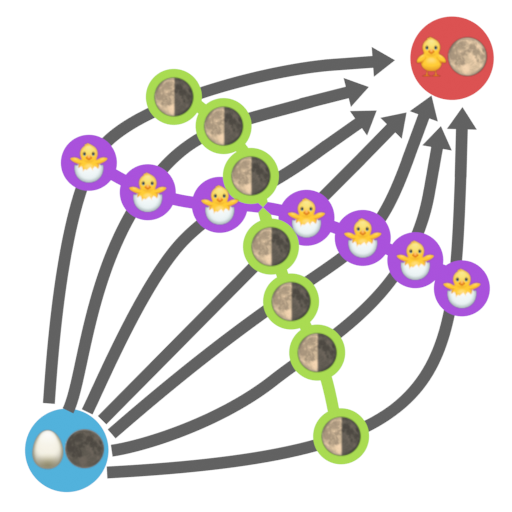

We start with an egg and a new moon, and some time (both horizontal and vertical) later get a chick and a full moon. The wobbly lines connecting both points in time are causal chains: they always advance up and to the right, meaning that all the points they visit form a well-ordered causal chain. For this reason, we will call them timeline-like lines. Each of these lines starts with an egg and a new moon, and ends with a chick and a full moon. So, for every one of them, there’s some point in which the events “egg hatching” and “quarter moon” take place. Let’s draw these point-events, for each timelike-line:

It’s now clear that events like “egg hatching” don’t happen at a single point in time, but rather at all points along a line. Like timeline-like lines, these lines have some constraints: no point of the line is the past or future of any other point (so, they can never advance in the up-right direction, only down-right). If not, there would be a timeline-like line which contained both points, meaning that that timeline would see the “egg hatching” event twice. We will call lines with this property event-like.

In 1D time, with point-like events, the order is always clear. However, in the diagram, there seems to be an interesting property of these event-lines: they can cross, meaning that the events aren’t objectively ordered. Is this some exciting property of 2D time? No: the event lines can cross only if their order makes no measurable difference. There can’t be a third object whose final state depends on the ordering of “egg hatching” and “quarter moon”: if there was, it would have a single state at the end, meaning that all timelike-line lines reaching that point saw the same order of events.

My main motivation for thinking about two-dimensional time was that the number of events that it could fit would grow quadratically instead of linearly. We now see that that isn’t the case: we added an extra dimension of time and in return got an extra dimension of events, leaving us back with a linear number of events. In this sense, a story in two-dimensional time loses nothing if you pick any timeline-like line inside and follow it, forgetting about everything that happens outside it. Oh well, the road here was kind of fun. Despite everything, if anyone finds or creates some game (or book, or anything) that uses a second dimension of time in an interesting and consistent way, I’d love to hear about it!